Continued from:Strategically dangerous: What Makes or Breaks CEOs ( I )

Be Number 1 or Number 2—-“Winner Takes All”?

Managers and executives often commit themselves to making the company “Number 1 or Number 2” in the industry. Former GE CEO Jack Welch’s famous ultimatum “Either be number 1 or number 2 in your industry, or get out!” was just one version of competition to be the best. This model is based on the idea of “winner takes all.” Managers and executives believe that companies win by getting bigger and, ultimately, by dominating their industries. If size drives competitive success, then growth is essential to achieving market share and volume. Companies pursue economies of scale and scope in the belief that these will be decisive in determining competitive advantage and profitability.

What makes this idea so dangerous is that there is, in fact, some truth in it, and also this goal (getting bigger) is a lot easier to measure. Before you assume that bigger is always better, it is critical to run the numbers for your particular business. Too often the goal is chosen because it sounds good, whether or not the economics of the business support the logic. In industry after industry, economies of scale are often exhausted at a relatively small share of industry sales. We’ve found no systematic evidence indicating that industry leaders in terms of market share are the most profitable or successful firms. June 1st, 2009, GM (General Motors) made the fourth largest bankruptcy organization in US history. General Motors was once the world’s largest car company for a period of decades, a fact that didn’t prevent its decent into bankruptcy. In contrast, BMW, small by industry standards, has a history of superior returns. Over the past decade, its average return on invested capital was 50 percent higher than the industry average.

Companies under the influence of winner-takes-all thinking tend to pursue illusory scale advantages by cutting price to gain volume or by overextending themselves to serve all market segments or overpriced mergers and acquisitions.

Companies only have to be “big enough,” which rarely means they ahi to dominate. Often “big enough” is just 10 percent of the market. However, the winner-takes-all model of competing presupposes incorrectly that there is one scale curve in an industry and that all companies must move down that curve—assuming that all rivals are competing to offer the universally best product or service. In practice, most industries exhibit multiple scale curves, each based on serving different needs.

“The Best” Good for Customers, or In the Middle of Nowhere?

But isn’t the “the best” good for customers? To answer this, we have to look at a concept called standard average.

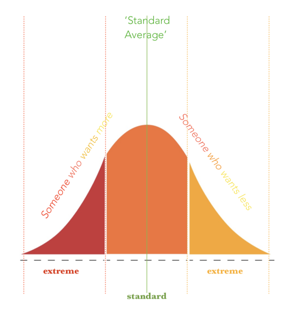

When companies compete to be the best, customers may benefit from lower prices as rivals imitate and match each other’s offerings, but they may also be forced to sacrifice choice. When an industry converges around a standard offering, the ‘average’ customer may do well. But remember that average are made up of some customers who want more and some who want less. There will be individuals in both groups who will not be well served by the average. If you look at the distribution of so-called “average”, you are going to notice that there is “standard average” that theoretically good for the average customers, but only so mathematically, not in reality. In reality, you are going to be encountered with dissatisfied customers from both ends, only slightly different in degrees. This is so simply because the needs of some customers may be over served by what the industry offers. They will pay more for features they don’t need. Most of the appliances in the kitchen and some consumer electronics have become unnecessarily complex and feature-laden. The needs of other customers may be underserved. Commercial flight meet the basic need of getting you where needed to be. But was it a pleasant experience? Are you eager to fly again?

So companies pursuing ‘the best’ eventually are heading to a the-middle-of-nowhere.

Competing to be Unique: It is All About Value

Competing to be unique is all about value. It’s about uniqueness in the value you create and how you create it.

Strategic competition means choosing a path different from that of others.

Competition to be unique reflects a different mind-set and a different way of thinking about the nature of competition. What makes this particularly hard is that often times managers and executives’ performance is not measured based on different or unique, but short term deliveries of the expected results, often, in this case financial output. Managers and executives who pursue distinctive ways of competing aimed at serving different sets of needs and customers. The focus is on creating superior value for the chosen customers, not on imitating and matching rivals. When companies start competing to be unique, they are creating more choices for customers, and because customers have real choices, price is only one competitive variable. Some competitors such as IKEA, will have strategies emphasizing low price. Others, such as BMW, Apple, or Four Seasons, will command a premium price by offering different features or service levels. Customers will pay more (or less) depending on how they perceive the value that’s offered to them.

a different way of thinking about the nature of competition. What makes this particularly hard is that often times managers and executives’ performance is not measured based on different or unique, but short term deliveries of the expected results, often, in this case financial output. Managers and executives who pursue distinctive ways of competing aimed at serving different sets of needs and customers. The focus is on creating superior value for the chosen customers, not on imitating and matching rivals. When companies start competing to be unique, they are creating more choices for customers, and because customers have real choices, price is only one competitive variable. Some competitors such as IKEA, will have strategies emphasizing low price. Others, such as BMW, Apple, or Four Seasons, will command a premium price by offering different features or service levels. Customers will pay more (or less) depending on how they perceive the value that’s offered to them.

Competing to be unique is, by nature, positive-sum competition, while competing to be the best is zero-sum competition. While zero-sum competition is rightly depicted as a race to the bottom, positive-sum competition produces better outcomes. Of course, not every company will succeed, because competition will weed out the underperformers. However, customers can get real choice in how their needs are met. Competing to be the best feeds on imitation while competing to be unique thrives on innovation.

Managers and executives need the right mind-set for competition, the mindset that encourages competing to be unique, rather than competing to be the best. Because there is nothing predetermined about the path that industries take to zero-sum or positive-sum competition. There is nothing inherent in the industry—whether it is high tech or not, whether it is service or manufacturing—that will determine its fate. Some industries do face tougher economic challenges than others, but the path that industries take is also the results of choices—-strategic choices—that managers make about how to compete. Bad choices unleash a race to the bottom. Good choices promote healthy competition, innovation and growth. So managers and executives have the power, in some degree, to influence the health of an industry in the end.

Managers and executives should beware of anyone who claims there is only one way to win. If there were only one best way to compete, many, if not all, companies would adopt it. Competition would end in stalement at best or mutual destruction at worst. Instead, competition is multidimensional, and strategy is about making choices along many dimensions, not just one. No single prescription about which choices to make is valid for every company in every industry. This is the same reason why emulation of Huwei is not recommended.

Competition is multidimensional, strategy is about making choice along many dimensions.

Being a manager and executive requires strategic thinking, a mindset that starts with understanding correctly what competition is before stepping into the competition that is a positive-sum game by nature.

Continued on:Strategically dangerous: What Makes or Breaks CEOs ( III )